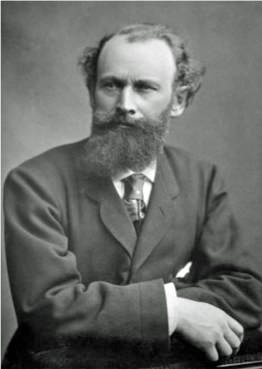

Édouard Manet |

Baudelaire and the Impressionist Revolution |

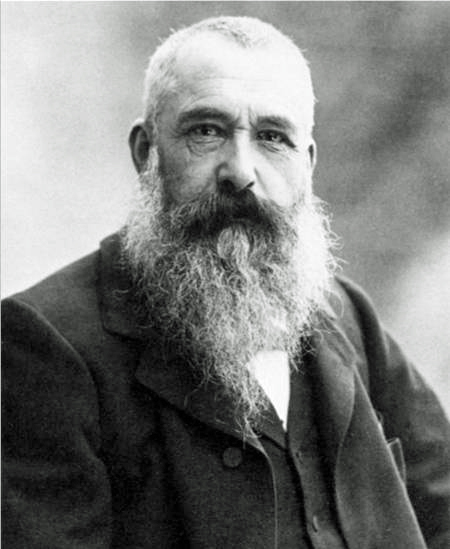

Claude Monet |

|

|

The Neoclassical Movement in French PaintingNeoclassicism was a widespread and influential

movement in painting that began in the late 18th century and reached its height

in the

work of the French painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). In France, the

movement lasted into the late 19th century with the last major neoclassical

painter being Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Neoclassical painting

generally took the form of an emphasis on austere linear design in the depiction

of classical themes and subject matter, using archaeologically correct settings

and costumes.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)During the early and middle years of the 19th century, Neoclassicism coexisted with the seemingly completely different and opposite style of Romanticism. However, far from being distinct and separate, these two styles intermingled with each other in complex ways; many ostensibly Neoclassical paintings show Romantic tendencies, and vice versa. This contradictory situation is strikingly evident in the works of the last great Neoclassical painter, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), who painted sensuous Romantic female nudes while also turning out very linear and static historical and mythological paintings in the approved Neoclassical mode. Perhaps most famous example of this latter class of neoclassical painting was a painting done by Ingres in 1827, entitled Apotheosis of Homer (see below).

Apotheosis of Homer (1827)

This huge Ingres oil painting, The Apotheosis of Homer , measures almost 13 X17 feet. The painting is symbolic of Ingres's belief in a hierarchy of timeless values that are based on classical precedent. Commissioned in 1826 as a ceiling decoration for the Louvre, it was completed and exhibited in 1827. Many years later, in 1855, it was removed from the ceiling and shown at the Paris Exposition of 1855 and then at the Luxembourg Museum. Finally, in 1874, it was returned to the Louvre but was hung as a wall painting, while a copy, still visible today, occupies its former place on the ceiling. The tiered, rectilinear structure of the work is better seen on a wall than a ceiling. The symmetry of the figures and architecture suggest the composition of Raphael’s wall frescoes, such as the School of Athens. Ingres's choice of this compositional scheme is consistent with the nature of his subject, the deification of a single genius to whom all subsequent generations are indebted. Like Zeus on Mount Olympus, Homer is located in splendid isolation at the apex of a slowly ascending pyramid of historical figures, both ancient and modern, who have come to venerate him. Seated just below the blind poet are personifications of the Iliad and the Odyssey, represented as a pair of very sturdy women who bear the attributes of a sword and an oar. Hovering above Homer is the goddess Nike, who crowns him with a laurel wreath. In the Ingres hierarchic pantheon of great men, the classical figures are placed in the higher middle stratum, where they are seen mainly in full length. They appear in mirror-image pairs: Aeschylus, with his scroll on the left, is reflected on the right by Pindar with his lyre; Apelles, with his brushes and palette, by Phidias with his mallet. Amid these classical giants, only two moderns are admitted: Raphael, who is led by Apelles, and Dante who is accompanied by Virgil. Seen below in half-length and cut off by the frame, are two trios of great seventeenth-century Frenchmen, who echo each other: Poussin, Corneille, and La Fontaine on the left; and Boileau, Moliere, and Racine on the right. At the lower corners, partly fragmented by the framing edge, three non-French writers are seen: at the left are Shakespeare and Tasso; and at the right is the one-eyed Camoens. Ingres greatly esteemed this work and, for many years prior to his death, he planned a new version of the painting that would enlarge the roster of great men. Some art historian say that Ingres's fiercest rival, the Realist painter Gustave Courbet, was influenced by this ambitious and consciously allegorical painting. Courbet's enormous 1855 painting of The Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory, shows considerable compositional similarity with The Apotheosis of Homer. The Courbet painting translated the classical deity amid his attendant worshipers into the no less centralized person of Courbet himself, set amid a vast assembly of respectful admirers.

|

|

|