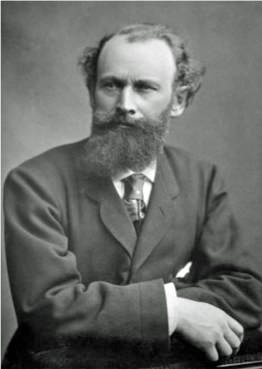

Édouard Manet |

Baudelaire and the Impressionist Revolution |

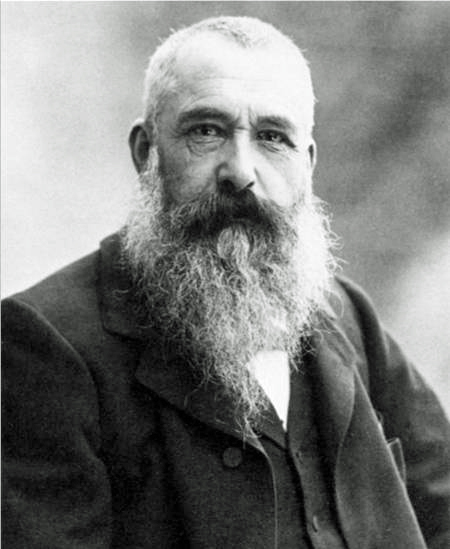

Claude Monet |

|

|

Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

In my opinion, Edouard Manet was the greatest European painter in the interval between Jacques Louis David (1748-1825) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). Manet's art cannot be classified within any of the great painting styles of the 19th Century. His work shows some elements from all of the artistic styles of his time, yet his paintings are unique. He was one of the first 19th Century artists to use scenes from modern-life as subjects. In a way, his art bridged the gap between Realism and Impressionism. However, he heavily influenced the Impressionists and they did everything possible to persuade Manet to join them in their exhibitions, but to no avail. In the last ten years or so of his life, he produced a number of painting executed in the Impressionist style, yet he never considered himself to be an Impressionist. One of his last major works, A Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882), shown below, is arguably the finest Impressionist painting of all time! Most of Manet's earlier works make use of the traditional techniques of the past. However, he was unique in his use of unorthodox composition and color, employing broad planes, and solid construction. As a result, he pointed the way toward the future of art. Unlike most of the Impressionists, he preferred painting in his studio rather than working in the open air. Also, he made considerable use of black pigment, that, in his works, became a true living color. His works were characterized by the use of clear colors, strong lines and large flat areas. His depiction of silhouetted figures have a background in monochrome and a clearly defined outline. Overall, his paintings were so well delineated and rounded in contour that they seemed almost to project outwards from the immediate foreground. Manet brought fresh inspiration and techniques to the observation of nature and contemporary life and ultimately served both as an influence and a stimulus for the Impressionists. Cafe gatherings were the main device used by Manet to communicate his ideas. In the 1860's, Manet was the leader of a group of artists who met regularly at the Parisian Café Guerbois on Batignolles Street, which was near Manet's studio. The group, consisting mostly of major writers and painters, usually gathered at the cafe on Sundays and Thursdays. Besides Manet, the group regularly included Henri Fantin-Latour, Émile Zola, Frédéric Bazille, Louis Edmond Duranty, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley. Sometimes Paul Cézanne and Camille Pissarro also joined them. This gathering was frequently referred to as The Batignolles Group. Many of the members were to become very important Impressionist painters. Fantin-Latour, who was not an Impressionist, has immortalized many members of this group in his painting entitled, A Studio in the Batignolles, shown below.

A Studio in the Batignolles (1870)

The above painting, made in 1870 by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), is entitled Un atelier aux Batignolles (A Studio in the Batignolles). The Batignolles was the district in Paris where Manet had his studio and many of the future impressionists lived there. The two individuals seated in front are the painter, Edouard Manet, and his model, sculptor Zacharie Astruc. They are surrounded by six standing figures, who, from left to right, are: painter Otto Scholderer who observes from the back of the room with serious attention; next is Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the only one wearing a hat, who stands out clearly against the empty frame behind him and who looks directly at the painting on the easel; next is the author and art critic, Emile Zola, who, holds his eyeglasses in his hand and directs his gaze in the opposite direction of Renoir's; next is the musician Edmond Maitre; next is the tall and commanding profile of French painter Frederic Bazille; last is Claude Monet who is inserted at the edge of the painting on the extreme right, almost as an afterthought. The painting was completed only a few months before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and public opinion in France was becoming decidedly anti-Prussian!. The only German in the group, Scholderer may have been shown as somewhat isolated from the others (who were all Frenchmen) due to his probable pro-Prussian leanings. Bazille would die in the War, thus ending a very promising painting career. The fact that Renoir's head is placed within the empty picture frame while looking directly at Manet's painting, may indicate that Fantin-Latour considered Renoir to be the probable successor to Manet. Fantin-Latour was a student of the Realist painter Courbet and a great admirer of the Neo-Classicist painter Ingres. However, this painting is not particularly realistic in portraying the atmosphere of an artist's studio. The costumes and décor are the epitome of sobriety. Fantin-Latour uses the severity of their costumes and gravity of their expressions to make them look serious and respectable. He also includes two objects in the scene that provide indicators of his aesthetic values. The statuette of Minerva symbolizes Truth and testifies to his respect for the Classical tradition; the Japanese-style vase indicates the admiration that most artists of his generation held for Japanese art. A Bar at the Folies Bergère (1882)

Edouard Manet completed his masterwork, A Bar at the Folies Bergère, in 1882. He submitted the painting to the 1882 Paris Salon where it was accepted. Even so, the work was judged controversial and was subjected to considerable derision by the artistic establishment of the time. The painting is oil on canvas and measures approximately 37 X 51 inches. This work is currently on permanent display at the art gallery of the Courtauld Institute in London and is considered to be one of the masterpieces of that museum. The Folies-Bergère opened in 1869 and is still located at 32 Rue Richer in the Montmartre District of Paris. In Manet's time, it was known as a middle-class brothel and as a place where illicit couples could meet more discreetly than at a hotel. The Folies-Bergère was a café, cabaret, and a circus with aerial acts and acrobats. Bourgeois men could go there to meet women of varying degrees of availability. It was open nightly and cost only two francs, no matter where one sat or stood. It attracted a wide range of customers, from shop clerks to bankers and prostitutes to high class courtesans. Manet was a frequent visitor; he would go there with his notebook and sketch for hours. One day he asked Suzon, an attractive and charismatic young woman who actually worked there, to come to his studio to pose for him. He drew her in uniform, a lace-trimmed, square-necked, tight-fitting velvet bodice over a long skirt. He also set up a marble-top counter to represent one of the many bars in the cabaret. The famous art historian T. J. Clark devotes an entire chapter in his book, entitled The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers, to a discussion of the painting. To him, the barmaid is: The face of fashion, which is a good and necessary disguise. Wearing the right makeup, the right earrings, the right hairdo, she cannot be identified as middle class or working class. For if one could not be bourgeois, then at least one could prevent oneself from being anything else.. . . The look which results is a special one public, outward. . . impassive. . . for to express oneself would be to have one’s class be legible. Much has been written about A Bar at the Folies-Bergère: Is the girl a prostitute? Is that a mirror behind her? Where is the man really standing? To some viewers the barmaid is heavily made up and gaudily dressed; to others she is pale with a lifeless face and a mediocre body. Most historians conclude that, since the Folies-Bergére was a market for prostitutes, any barmaid working there must have been one. This barmaid is not necessarily what she may appear to be. A comparison of her frontal image with her reflected image conveys the tension between what she represents to an ordinary customer and how the painter sees her. The barmaid does not even acknowledge the patron’s presence or the viewer’s glance; nothing suggests that she might be available, except her presence in that place. Manet was well versed in classical iconography and provides clues as to her identity. The roses located in the right foreground are not without meaning. The rose was sacred to Venus in antiquity and is her attribute in Renaissance art; It also is associated with the Virgin Mary in religious paintings. To make sure that these aspects were noticed, Manet placed a white rose, symbol of purity, beside the pale pink one, a symbol of divine love. Both are in a glass of water on the bar -- a vessel of water is another traditional symbol of purity. Also, two white roses appear in the barmaid’s corsage. I believe that Manet intends the painting to convey a modern image of an ancient deity. She also may be a representation of a female dandy. Her impassive expression under the scrutiny of the patron recalls Charles Baudelaire’s description of the dandy. The barmaid's alienation is communicated by the way that she seals herself off from her surroundings. She is detached. She is impervious to the customer’s assumption that she can be bought. The man's glance, seen only in the reflection, attempts to fix her image as a commodity. But Manet contradicts him; he depicts her unresponsiveness and qualifies her with roses. A crystal bowl of what are apparently oranges is shown on the bar. While Manet was working on the painting, he received a gift from a client, a crate of tangerines. The tangerines were in the studio when he painted the still life on the bar and if you look closely, the fruits assumed to be oranges are in fact tangerines, for they are flatter and glossier than oranges. The tangerines provide an important note of color and also make another iconographic association. The orange was a common substitute for the apple in biblical and Christian iconography. What is closer to Venus’s golden apple than a bright orange (or its near twin, a tangerine)? In my view, Manet has not described just a modern barmaid; he has also given us a Venus, not a mediocre nude, but a dressed Venus, a modern Venus, difficult to recognize, but still deserving of golden apples. Manet’s barmaid is a modern goddess, not of true love but of the illusion of love. A Bar at the Folies-Bergère was Manet’s last large-scale work -- it was his monument to the Paris of his lifetime!

|

|

|