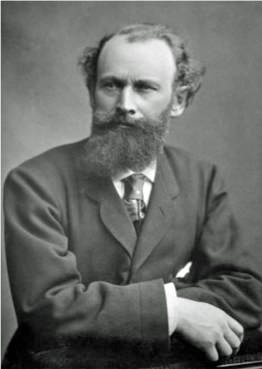

Édouard Manet |

Baudelaire and the Impressionist Revolution |

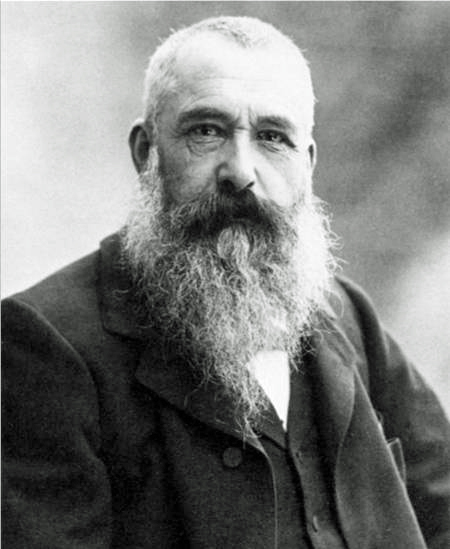

Claude Monet |

|

|

Philosophy of RealismThe Realist Movement in French art flourished from the 1840's to the 1890's. Realists believed that the main purpose of literature, painting and even music, was to communicate truthful and objective views of modern life. French Realism emerged after the Revolution of 1848 that overturned the monarchy of Louis-Philippe; the movement continued to develop during the Second Empire of Napoleon III. The Realists supported democratic reform of the political system and desired the democratization of art by depicting modern subjects drawn from the everyday lives of the working class. They rejected the Classicism of academic art and the unrealistic, exotic themes of Romanticism. Realism was supposed to be based on direct sensory observation of the contemporary world. Realist painter, Gustave Courbet, asserted that painting was essentially a concrete art that should only deal with the representation of real and existing things. Realist artists recorded in grim detail the frequently unpleasant life experiences of humble people. Examples of Realists in literature include Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac, and Gustave Flaubert. At the same time, Realist philosophers adulated the working classes. For example consider the socialist philosophy of Pierre Proudhon and Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto, published in 1848, which urged a proletarian uprising.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)Gustave Courbet is the principal painter who championed the cause of Realism. Prior to his time, most French paintings were composed of attractive pictures that made life look much better than it really was. Courbet, in spite of intense opposition, attempted to accurately portray ordinary places and people. Gustave Courbet was born in 1819 to a prosperous farming family in Ornans, France. He went to Paris in 1841, supposedly to study law, but soon he decided to study painting. In 1844 his self-portrait, Courbet with a Black Dog, was accepted by the Paris Salon, the annual public exhibition of art sponsored by the influential French Academy. The 1848 political revolution in France brought with it a cultural revolution and the public became more open to new ideas in the arts. Only a year later, in 1849, Courbet produced one of his greatest realist paintings, The Stone-Breakers (see below). In 1855 he completed a huge canvas titled Real Allegory of the Artist's Studio (see below); when it was refused for inclusion in the Paris Salon for that year, Courbet boldly displayed this work as part of a personal exhibition located in a building near the Salon exhibition hall. By 1859 Courbet was the undisputed leader of the French realist movement. He painted all varieties of subjects, including admirable portraits and sensuous female nudes but, most of all, scenes of nature. His series of seascapes with changing storm clouds wafting overhead, begun in the 1860's, greatly influenced the young Impressionist painters of the time. Politically a socialist, during the time of the Paris Commune in 1871, Courbet took part in certain revolutionary activities for which he was imprisoned for six months. He was also assessed a severe fine which was more than he could pay. He fled to Switzerland where he remained until his death on 31 December 1877.

The Stonebreakers (1849)

Courbet completed The Stonebreakers in 1849. This oil painting, measuring 63 X 102 inches, was quite unlike the classical and romantic pictures of the time; it showed poor peasants from the artist's native region in a realistic setting instead of rich bourgeoisie in glamorized situations. Painting had previously been mostly reserved for the depiction of elevating themes from history and mythology. When The Stone Breakers was exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1850, it was attacked by the French establishment as being inartistic, crude, and even socialistic! Indeed, the contemporary socialist writer, Pierre Proudhon, approved of the painting and described the man with the hammer in the following terms: "His motionless face is heartbreakingly melancholy. His stiff arms rise and fall with the regularity of a lever. Here indeed is the mechanical or mechanized man in the state of ruin to which our splendid civilization and our incomparable industry have reduced him... This modern servitude devours the generations in their youth: here is the proletariat." Unfortunately, the work was destroyed during World War II.

Real Allegory of the Artist's Studio (1855)

Gustave Courbet completed the above painting in 1855 and submitted it and other paintings to the International Paris Exhibition, but all of his works were rejected. Undaunted, he rented a hall just outside of the Paris Exhibition site, and displayed his work at his own personal exhibition! The huge oil painting, measuring almost 12 X 20 feet, bears the incredibly long title of: Allégorie réelle: intérieur de mon atelier, déterminant une phase de sept années de ma vie artistique (The Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory Summing up Seven Years of My Artistic Life). It now hangs in the Musee d'Orsay in Paris. The painting is organized as a kind of triptych executed in the Realistic artistic style. In the center is Courbet himself, the foremost advocate of Realism. He is painting a landscape of his own Franche-Comté countryside. Just behind Courbet is an unidealized nude model. to his front is a peasant boy, who watches the master at work with admiration while a white cat plays at his feet. The right side of the triptych is a group of bourgeois individuals who have influenced and supported Courbet. Some of them may be identified: The standing figure facing to the left is Alfred Bruyas, Courbet's longtime patron. Behind Bruyas is another friend, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the French socialist philosopher. The man seated to the left of Proudhon is the French novelist Jules Husson (pen name - Champfleury), who was an early advocate of Courbet's Realism. The figure on the extreme right is the French poet Baudelaire; his image is based on a portrait that Courbet had painted of the poet in 1848. Just to Baudelaire's right is the erased image of Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire's quadroon mistress. Her erased presence was seen during a recent x-ray cleaning of the painting. Courbet painted over her image at the specific request of his friend Baudelaire. The identity of the prominently displayed bourgeois lady in the shawl is uncertain. Some have contended that she is French novelist George Sand; however, there is little resemblance to known portraits of that famous lady. Courbet called this lady and the man standing to her right as "amateurs mondains." The left side of the painting contains a group of people, mostly of the lower classes, that Courbet may have used as models for many of his earlier paintings. On the ground beside the canvas sits the figure of a starving (probably Irish) peasant, the Great Irish Famine having taken place only a few years earlier. Behind the peasant, are several other figures who appear to include a priest, a prostitute, a grave digger and a merchant. The standing figure on the extreme left appears to be a Jewish Rabbi. Seated in front of the Rabbi is a the hunter with several dogs.

|

|

|